A Voice from that Great Cloud of Witnesses

A few lessons from T.S. Eliot's "After Strange Gods"

Each generation is tested by its own tumult. -Randy

We live in tumultuous times. Oddly enough, our turmoil doesn’t exist in the everyday events of our lives, but in our cultural conversations about larger issues that exist in the latest media and social media battles:

Trump, tariffs, and ICE

Israel, Hamas, and the plight of the Palestinians

White House renovations, Putin, and Ukraine

Government shutdowns and whatever will come tomorrow.

If we try to live our everyday lives according to the latest headlines, we begin to go a bit crazy; some of us seem well on our way. How, then, do we live in the midst of constant anger yet keep our sanity? Obviously, we turn to a poet and playwright giving a lecture in Virginia in 1933 for an answer!

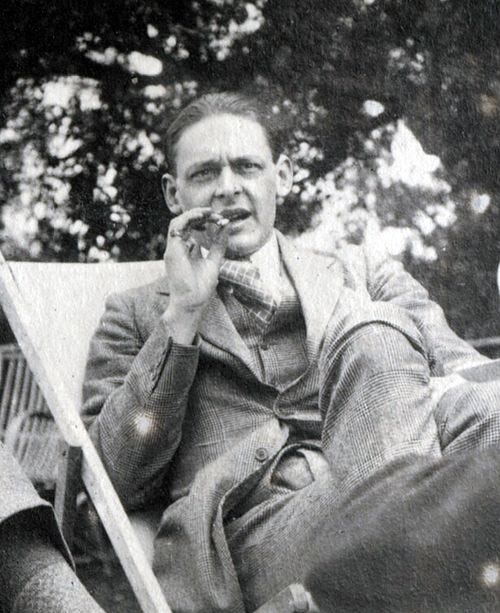

Each generation is tested by its own tumult. In 1933, for example, people had to makegoodhappen while Hitler was consolidating power, as they personally struggled to make ends meet in a global depression. At the same time, 40% of voting Americans watched the inauguration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the president they had voted against. Perhaps they escaped their fear of the future by watching the premiere of the movie, King Kong. But when they left the theater, they still had to re-enter a society that had tried and repealed prohibition and a world which saw the establishment of the first concentration camp in Dachau, Germany. Yet this was when T.S. Eliot, in response to an invitation by the University of Virginia, took the podium and attempted to makegoodhappen in three lectures. They were good enough to be published in a slim volume with an oversized name: After Strange Gods: A Primer of Modern Heresy. Though the title is rather theological, his concern was much wider still.

Eliot gives us a way to keep balance as we experience today’s tumult, adaptation, and change. The temptation in such times, his as well as ours, is to erase our past as unworthy and start anew with a clean slate. Eliot argues that leaving centuries of religious, national, cultural, and familial traditions leaves us with little more to guide our actions than personality and emotion.

Eliot’s point is embarrassingly obvious in our day. The political vitriol on the left and right has no problem expressing strong opinions, but has great difficulty grounding itself in everyday life. There is ample evidence that our emotional activism has failed to makegoodhappen. The root of the problem is the assumption that we can remove ourselves from traditions that gave us birth.

By leaving all tradition behind, we become heretics who have turned to strange gods. We reject our world and commit to doing the opposite of what we were brought up to believe. If “they” think this, “we” think that. If “they” do this, “we” do that. They become a mirror image of the tradition they purport to reject. They’ve no existence in themselves but are rather “phantom negatives.” If we are going to makegoodhappen in our day, we must find a different path. Here are a few suggestions to begin with:

Eliot’s view of tradition is reflected in the Bible. Jesus didn’t create his own material ex nihilo. One of his major sources for concepts and ideas was the book of Isaiah. Isaiah didn’t speak his prophecies from the “clean slate” of his own personal emotions. He and the other prophets worked out of the covenant God made with Moses, which itself developed out of the promise made to Abraham. As Paul describes it, we (mostly) Gentile followers were grafted into this family tree and their story through faith in Jesus Christ.

Our relationship with Jesus, expressed in the habits and responsibilities of everyday life, is lived within our adoption into the family of Abraham. We cannot disconnect faith from this story without reducing our Christianity to individual personality and emotion.

Faithfulness in our journey requires us to synthesize and combine, an ability that, as T.S. Eliot puts it, “…comes from deep study and comprehensive knowledge” of the Scriptures. We should become experts in the Bible, not in the sense of dissecting it, but by understanding its implications and applying it creatively to everyday life.

I’ve always believed in doing everything I can to avoid life’s landmines. The wisdom of previous generations is helpful in that regard. That great cloud of witnesses has much to teach us, either by having stepped on landmines and learning from the fallout or by having experienced the benefits of deftly stepping over them. T.S. Eliot is no exception. A final quote from him:

“I wish that I might be able to encourage…(people and organizations) to maintain their communication with the past, because in so doing they will be maintaining their communications with any future worth communicating with.”