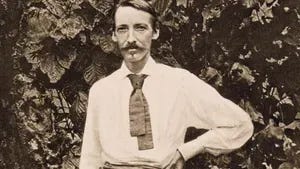

Robert Louis Stevenson's "The Torch-Bearers"

Summer Short Story: Part Three

“…the true realism, always and everywhere, is that of the poets: to find out where joy resides, and give it a voice far beyond singing.” R.L. Stevenson

Most of our news and entertainment seeks attention by emphasizing the sensational. We return to their concise and conspiratorial messages again and again because they calm our fears by confirming our prejudices. The whole process is a feedback loop that satisfies us in the short term but reinforces our insecurities in the long term. It is ultimately self-defeating.

By contrast, our summer reading urges us to shift our focus to the plain events and everyday people in front of us. “The Torch-Bearers” isn’t easy reading. It includes unfamiliar vocabulary and literary references. Stevenson’s essay is written in a style requiring more study and patience than does the information we normally consume. Over the past century authors and literary critics like G.K. Chesterton have cited the importance of this essay in its unusual ability to revive a sense of wonder in its readers. We can still find this sense of wonder today. It can do much to heal our souls.

Reading this essay a few times has resurrected my experience of finding joy in everyday life. It reminded me of experiences I’ve enjoyed among people with real happiness, faith, and contentment in a Colorado Prison, a Nicaraguan village, and a Mexican border town. I wonder what life experiences will surface for you as you read the third and final section of Robert Louis Stevenson’s "The Torch Bearers.”

“The Torch-Bearers” part 3 with overlap from part 2.

The case of these writers of romance is most obscure. They have been boys and youths; they have lingered outside the window of the beloved, who was then most probably writing to some one else; they have sat before a sheet of paper, and felt themselves mere continents of congested poetry, not one line of which would flow; they have walked alone in the woods, they have walked in cities under the countless lamps; they have been to sea, they have hated, they have feared, they have longed to knife a man, and maybe done it; the wild taste of life has stung their palate. Or, if you deny them all the rest, one pleasure at least they have tasted to the full—their books are there to prove it—the keen pleasure of successful literary composition. And yet they fill the globe with volumes, whose cleverness inspires me with despairing admiration, and whose consistent falsity to all I care to call existence, with despairing wrath. If I had no better hope than to continue to revolve among the dreary and petty businesses, and to be moved by the paltry hopes and fears with which they surround and animate their heroes, I declare I would die now. But there has never an hour of mine gone quite so dully yet; if it were spent waiting at a railway junction, I would have some scattering thoughts, I could count some grains of memory, compared to which the whole of one of these romances seems but dross.