Superstition

Compendium Entry No. 6: on our use of "Fundamentalist," "Evangelical" and "Christian Nationalist."

Christianity has become a phantom in the Western mind. Our intellectuals insist that this generation’s relative disinterest in the Biblical stories is a sign of cultural advance. But Jesus’ ghost still haunts us. You can hear it in our language.

“I have difficulty imagining citizens of a country strongly influenced by Buddhism hurling “Siddhartha Gautama” at each other in anger and upset.”

“Jesus Christ!” yelled the mother of an elementary-aged child as she jumped up from her coffee shop chair. As a Presbyterian pastor, I was accustomed to the name. But, for the same reason, I was surprised that she said it with such fervor. Her mini-skirt had not protected her legs from the metal chair she had just sat on, heated as it was by the noonday sun. Knowing that she wasn’t a follower of Jesus, I was unsure whether she used this phrase because she was meeting with a minister or from sheer force of habit. Whatever the reason, she was not alone in her choice of the Christian Son of God as the vehicle to express hurt and anger.

Though fewer of us believe, we continue to use the Christian Deity magically. It’s common to imbue the name of the Son, or the Father for that matter, with the power to curse people or things that we fear. It is an unusual use of a god. I have difficulty imagining citizens of a country strongly influenced by Buddhism hurling “Siddhartha Gautama” at each other in anger and upset. I feel confident that no one in Hollywood’s Scientology community would cry out “L. Ron Hubbard” in a similar situation. But the Christian deity has “pride of place,” diminished in our minds from a living being whom we honor to a magical spell we speak out loud, in public, whether or not we think that God exists.

Previous generations of English-speaking Christians worried about this very thing. They were accustomed to speaking of the third person of the Trinity as “The Holy Ghost.” Over time, however, “ghost” became commonplace in their language, for “the phantasmic residue of a dead person.” To prevent this diluted definition of the English word from spreading and becoming a superstitious understanding of the third person of the Trinity they changed their own phrase from “The Holy Ghost” to “The Holy Spirit.”

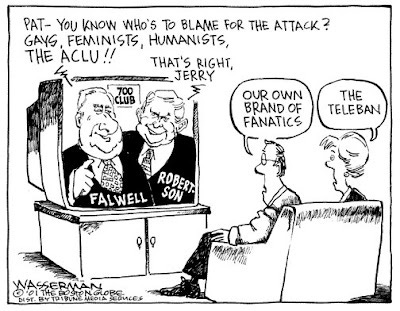

In our day, however, wordsmiths are less concerned about resurrecting the Christian God than warding off an evil that haunts us. I became aware of this project when the Moral Majority was a rising political power. Their success had attracted the ever-seeing eye of the press corps. In media descriptions, Jerry Falwell and his minions in the Moral Majority were gathering in dark places across the country to stir their witches’ brew of religion and politics. They were a clear threat to the republic. These Christians, or rather, these “bad Christians, were labeled “fundamentalists.”

The Moral Majority was short-lived. But Falwell paved the way for conservative Christians to become politically active in a variety of forms. In time our public discourse settled on a new name for the “bad Christians.” “Evangelical Christians” were the new alchemists whose nefarious combination of politics and religion threatened the progress of our country. Again it was the press’s moral responsibility to warn the public of this new haunting.

Today a new label is being deployed against the “bad Christian.” As one well-known Democratic strategist recently put it, this new designation is a bigger threat to our country than al-Qaeda. They are called the “Christian nationalists.” I remember when I first heard this term. I was working on my upcoming book, “Outside of the Church and Inside of the Faith,” with a secular Jewish woman who was my mentor in all things “Amazon publishing.” She brought up the term as we were discussing the difference between my Christian faith as described in the book draft and the faith she had heard about. She told me that Christian nationalists were a growing group of Christians who planned the forced conversion of Americans to Christianity. She spoke with real fear in her voice. I was surprised and concerned at the level of her concern.

These threats are so different from the Christian threats I’ve worked with for decades. Church attendance in the United States has been in decline since the late 1950s. In 2019, four thousand five hundred Christian churches closed their doors. Pew Research projects that the percentage of self-professing Christians in 2070 will decline to 50%. In 1972 that number was at 92%. The idea that our congregants would somehow take over the country didn’t exist in our wildest dreams. We pastors were kept up at night by the nagging fear that we were accompanying Western Christianity through hospice to its inevitable end.

I do not doubt that there are some Christians accurately described by my publishing mentor. I’ve met a few over the years. But they were all odd, disorganized, and very much in the minority. When I hear descriptions of Christian nationalists, I am reminded of the recurring fear of catastrophe that people in Southern California have when we see a decent-sized rainstorm. I think of the ways that the conservative media describes the rise of homelessness in our major cities as if this were proof of our nation’s demise. As Christianity has devolved in influence in this country, it has become a greater threat, a threat to the very existence of our nation. All of these “boogie-men” seemed connected. They all feel like superstition.

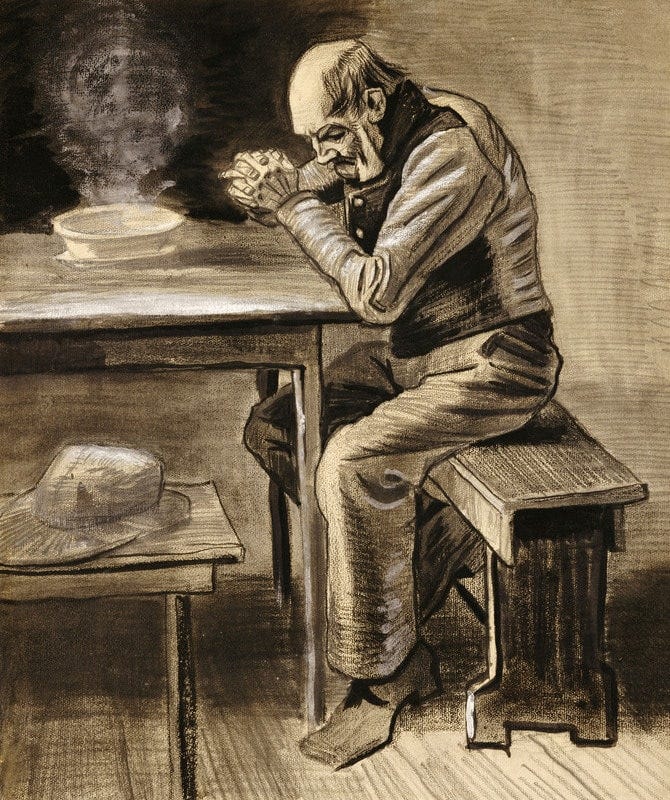

I’ve had to learn how to see this haunting that so many other citizens see because my own experience with Jesus has been so radically different. He is the one who has made sense of the world, who cast out my fears, who has given me a full and wonderful life. None of this happened through coercion, in any form, but through my own decision to follow him. One of the biggest challenges I have had as a Christian is to convey this experience to others. Where they see a ghost I see someone who is fully human and fully God, a person who is kinder, more loving, and more gracious than anyone I’ve ever known.

But it’s not unusual, when my commitment to Jesus becomes visible in public, that I’m stereotyped as a “bad Christian.” One afternoon, when I was at the first meeting of a civic committee at another coffee shop in the neighborhood. When the chair of the committee, working on a local arts project, introduced me as the pastor of a nearby church the other committee members visibly stiffened. One man could not hold in his distress, blurting out, “What is your church’s policy on Gays and Lesbians?” I tried to explain that my congregation was not in the community to set policies on different demographic groups in the neighborhood. My response did not satisfy him.

“Why am I, a young pastor in a small and declining congregation, such a threat to you?”

In a barrage of follow-up questions, he learned that I’d been married to my wife for the same amount of time that he had been living with his partner. “Is my relationship with my boyfriend as valid as your relationship with your wife?” he asked threateningly. I should have taken a page from Jesus and responded to his questions with a few questions of my own. “Why distract our meeting with this issue?” “Why is it so important for you to have my validation, in this progressive neighborhood which sees your relationship as equally valid, if not superior, to my traditional marriage?” “Why am I, a young pastor in a small and declining congregation, such a threat to you?”

This is a peculiarly Western haunting. Outside of the Western mind, Christianity is a growing grassroots, multiethnic community that chooses to follow the resurrected Jesus across boundaries of national citizenship, political affiliation, and ideological commitment. It’s been estimated that one in eight people around the world will choose to be a part of this movement by 2050. They will not be fundamentalists, evangelicals, or Christian nationalists. They won’t fit into our superstitious categories. They will be followers of the resurrected and ascended Christ, called away from their ghosts, their magic, and their fears to form communities of faith, hope, and love, in anticipation of the coming Kingdom of God. But in our hands, their story only seems to empower our superstitions and harden our stereotypes. In days gone by it had the power to fascinate our best thinkers and inspire the hopes and dreams of our greatest artists. If we turn from our haunting and choose to join them, we will find that their story still has the ability to animate and enlighten our everyday lives.

All I can say is wow! This is my first reading of yours, and I’m blown away by how amazing and eye opening it is. So much depth and so much truth. God bless you 🙏🏾