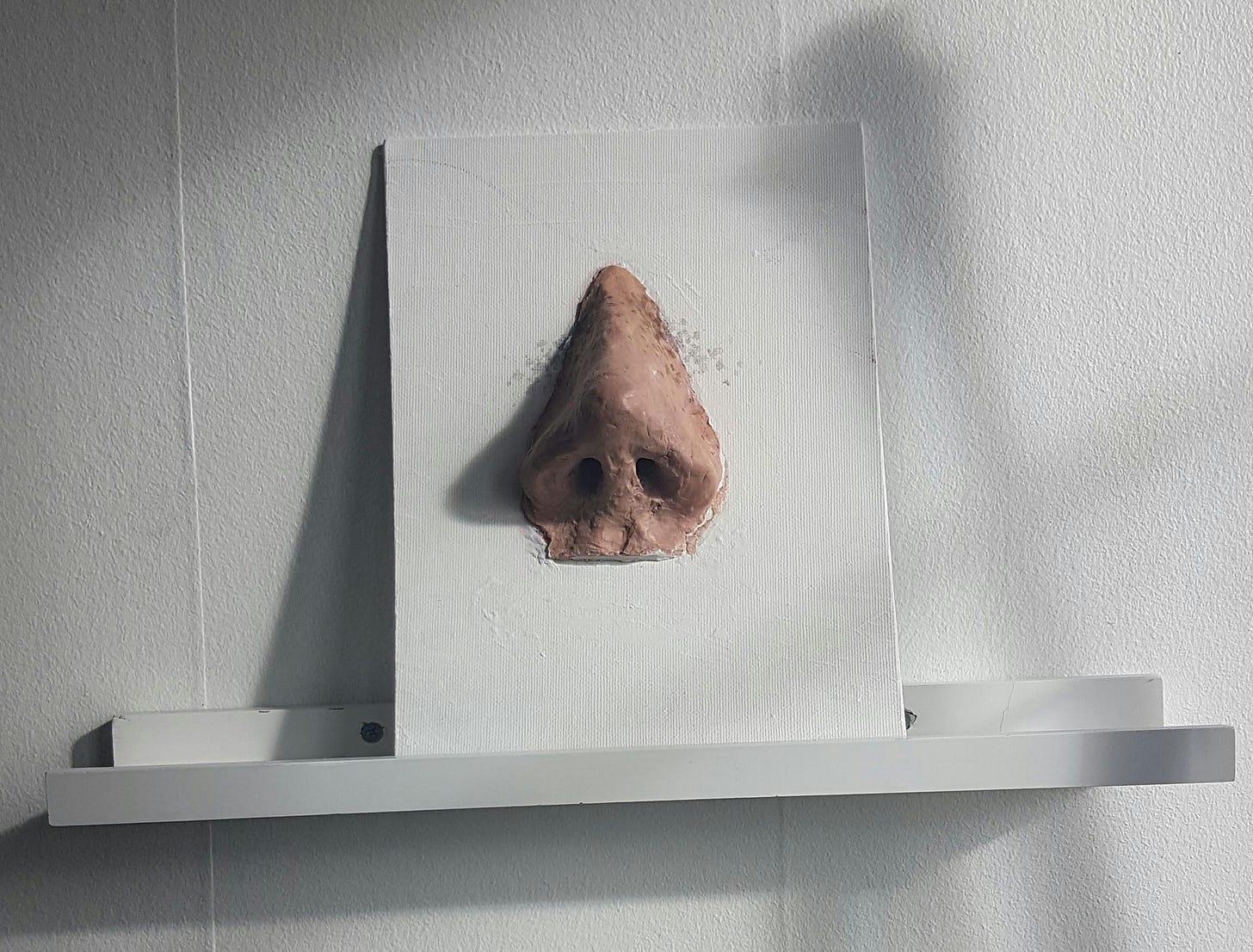

Cutting Off Our Nose to Spite our Face

A 21st Century Reflection on Dickens 19th Century "A Christmas Carol"

… It is good to be children sometimes, and never better than at Christmas, when its mighty founder was a child himself. -Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol1

It’s as plain as the nose on our face. The greed and stinginess of Ebenezer Scrooge, when we first meet him at the beginning of A Christmas Carol, have the upper hand. We no longer celebrate, freely and overtly, the birth of Christ; it is far safer to focus on the weather. Christmas has become a problem for the West. Presumably, if Dickens’ Carol were written today, it would have to be entitled, “A Winter Carol.”

Christmas markets in 21st-century London decline to mention the word “Christmas” in their publicity. In Hyde Park, a key location in Dickens’ novel, Barnaby Rudge, the Christmas market is billed as the “Hyde Park Winter Wonderland.” This move away from “Christmas” goes still deeper. In Portsmouth, where Dickens was born, the Portsmouth City Council has banned Christmas wreaths on communal doors and hallways due to fire safety rules. If you complain about this change, you will surely put someone’s nose out of joint. If their decree is not followed, the wreaths could be removed and you could be personally fined.

Yet, these changes shouldn’t surprise us. They have been happening for decades, right under our noses. Even the church has been colluding, unawares, in this move toward a stinginess of spirit at the end of each year. I recall, while in seminary, studying theological critiques of Western Christmas celebrations, learning to see the lights in the yards, the gifts under the tree, and seasonal greetings as problematic at best and self-concerned and consumeristic at worst. I joined in the idea that these traditions somehow tainted the celebration of Jesus’ birth. In words that I remember today with some embarrassment, I spoke confidently against the amount of money people spent during the Christmas season; there was too much food, too many decorations, too many gifts in the season. In self-righteous words that sound too much like the words of Judas, I cried, “What about the poor?”2 I couldn’t see beyond the end of my nose. I completely missed the importance of this traditional celebration of Jesus’ birth to our culture as a whole.

Dickens, however, saw the deeper meaning and value of Christmas. As Scrooge’s nephew says early in the story:

I am sure I have always thought of Christmas time, when it has come around - apart from the veneration due to its sacred name in origin, if anything belonging to it can be apart from that - as a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open up their hearts freely, and think of people below them as if they really were fellow passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys.3

That description of Christmas is right on the nose.

Charles Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol while on holiday in Italy. While surrounded by the beauty of endless summer, his mind focused on the Christmas tradition of Merry Old England.

As G.K. Chesterton said in his biography of Dickens, the Englishman’s home is his castle. Though consisting, like the home of the Cratchet family, of small winter feasts in small rooms, it was a place of defiant pleasure, and never more than during the Christmas season. The fire of the home hearth, the provisions for eating and drinking, the prayers of goodwill, formed together as a cosiness which defended the family against harsh winter weather and roaring rains. The holy day was a holiday from the challenges and difficulties of life.

Our Western predicament only amplifies the notes of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. In the 19th century, his story depended on the dark background of anti-Christmas sentiment. The Scrooge we meet at the beginning only heightens the contrast with the Ebenezer of the final stanza of the story. Comparing the before and after of Ebenezer Scrooge’s life proclaims the possibility loudly, in our day as well as in his, of melting hearts of stone and turning them into hearts of flesh.

For example, when the first spirit that visits Scrooge urges him to walk with him out the two story window of his home, Scrooge I am a mortal…and liable to fall. The spirit replies, poignantly, Bear but a touch of my hand “there,” said the Spirit, laying it upon his heart, and you shall be upheld in more than this!4

Later, when the ghost of Christmas past reviews his life, Scrooge sees an interaction he had with Belle, his betrothed, You fear the world too much, she answered, gently. All your other hopes have merged into the hope of being beyond the chance of its sordid reproach. I have seen your nobler aspirations fall off one by one, until the master passion, gain, engrosses you.5

As the third spirit visits and the notes of The Christmas Carol rise to their soaring climax, we hear Ebenezer’s heartfelt cry, "I will honor Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year.”6 Scrooge has changed and has become a generous and kind person. The final words of The Christmas Carol confirm this: Scrooge was better than his word. He did it all and infinitely more…and it was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well…7

Dickens had a real nose for the heart of Christmas and knew that some would abuse it. The second of the three spirits in his story says: There are some upon this earth of yours…who lay claim to know us, and who do their deeds of passion, pride, ill will, hatred, envy, bigotry, and selfishness, in our name, who are as strange to us and all our kith and kin, as if they had never lived. Remember that, and charge their doings on themselves, not us.8

Before we lose the power to influence human affairs forever,9 let us choose, not to cut off our nose to spite our face, but let us celebrate this Christmas season as well as the converted Scrooge did. May this season be a moment in time when we let go of our battles, focusing instead on making merry and giving to others. Our swords and shields will be waiting for us at the threshold of the new year. And who knows? If we join in with Tiny Tim in observing, God bless us, Every One! we may win the West over again to the real meaning of Christmas, even if only by a nose.

The Works of Charles Dickens, Volume II, (New York: P.F. Collier), 1870. p. 246

Ibid., p. 234

Ibid., p. 238

Ibid., p. 241.

Ibid., p. 251

Ibid., p. 253

Ibid., p. 243

Ibid., p. 237. (The ghost of Scrooge’s business partner, Jacob Marley, said that he had forever lost the power to interfere in human affairs.)

This is a wonderful piece that helps put in perspective the reason for the season. God bless you❤️✨️

Such a beautiful essay for the most precious time of year! Yes, let's celebrate Christ's birth with all the joy that we have! Wishing you and your family and lovely and peaceful Christmas, Randy.