Jesus and the Wizard of OZ

Why it's better to have four gospels than one.

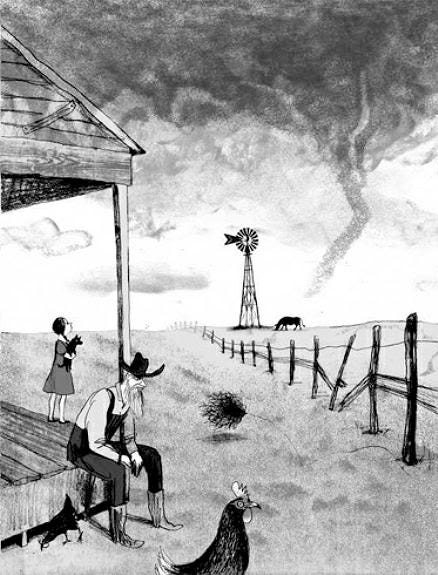

"No matter how dreary and gray our homes are, we people of flesh and blood would rather live there than in any other country, be it ever so beautiful. There is no place like home.”1