A Christian's Habits: Chapter Thirteen

The Habit of Decision.

“I know your deeds, that you are neither cold nor hot. I wish you were either one or the other! So, because you are lukewarm – neither hot nor cold – I am about to spit you out of my mouth.” -The Risen Jesus1

Randy’s Introduction

Nobody wants to make the wrong decision. That’s what Descartes was trying to avoid when he coined the phrase “I think, therefore I am.” He shut himself alone in a room, peeled back everything of which he was uncertain, and concluded that the only thing he could be sure of was that he and his thoughts actually existed. Of course, that didn’t stop other philosophers from deciding that they weren’t sure that Descartes ever existed, or, for that matter, that they exist. As in the movie “The Matrix” it could all be a fabrication. Thankfully Speer offers us an alternative to this existential navel gazing. We should simply take our uncertainty head-on by making a decision.

There’s a real benefit to this practical approach. If we make a decision and act upon it we’ll find out, sooner or later, whether we are right or not. Of course, taking this approach requires us to be willing to be wrong and to admit it, a skill that seems a bit rare in our day. But if we sincerely seek the way forward through decision and action we will find our way eventually.

And that’s not the only advantage of this approach. If we take Speer’s advice and make a habit of making decisions we will find a really valuable human quality developing within us. This process of making decisions in the face of uncertainty, testing their validity with action, and then pushing forward when we are right, even when fear and doubt push against us, makes us courageous people. And who doesn’t want to be a courageous person?

In the chapter that follows, Speer urges us to develop the habit of deciding which will strengthen our courage. So without further ado, chapter 13 of Speer’s “A Christian’s Habits,” “The Habit of Decision.”

I. Definitions

What decisions have you made about your life?

The word decision occurs in only one place in the Bible.2 That is in the third chapter of Joel. “Multitudes, multitudes in the valley of decision! for the day of Jehovah is near in the valley of decision.” This was the valley where issues were settled and judgement was to be passed. To that momentous time Jehovah was bringing the nations. In that valley is where all men are.

And so, though the word occurs only here, in the prophecy of Joel, the idea of the significance of our choices, and the importance and supremacy of the act and character of decision is everywhere in the Bible. God is shown to us as the great chooser, the One who deals with men and nations with positive and firm decisions. He is spoken of thus twenty-eight times in Deuteronomy alone. And the true man is set forth as the chooser. “I have chosen the way of faithfulness,” he says. “Thine ordinances have I set before me. I cleave unto thy testimonies3…Let thy hand be ready to help me; for I have chosen thy precepts.”4 This was the glory of Daniel and his friends. When they joined the young men in the king’s court, they decided that they would not defile themselves, and when, later, they were put to the test of fidelity to their God, they met the test with unflinching decision. To the threat of the fiery furnace they solemnly replied: "Our God whom we serve is able to deliver us from the burning fiery furnace; and he will deliver us out of thy hand, O king. But if not, be it known unto thee, O king, that we will not serve thy gods, nor worship the golden image which thou hast set up.5 Decision was the redeeming quality in the unjust steward.6 And it was the splendid thing in Paul. He was always straightforward, clear-cut, decisive. It was not his habit to temporize and dawdle. It was his habit at once to seek the will of God and to do it.

II. Wabbling: the Opposite of Decision

What commitments do you struggle with making?

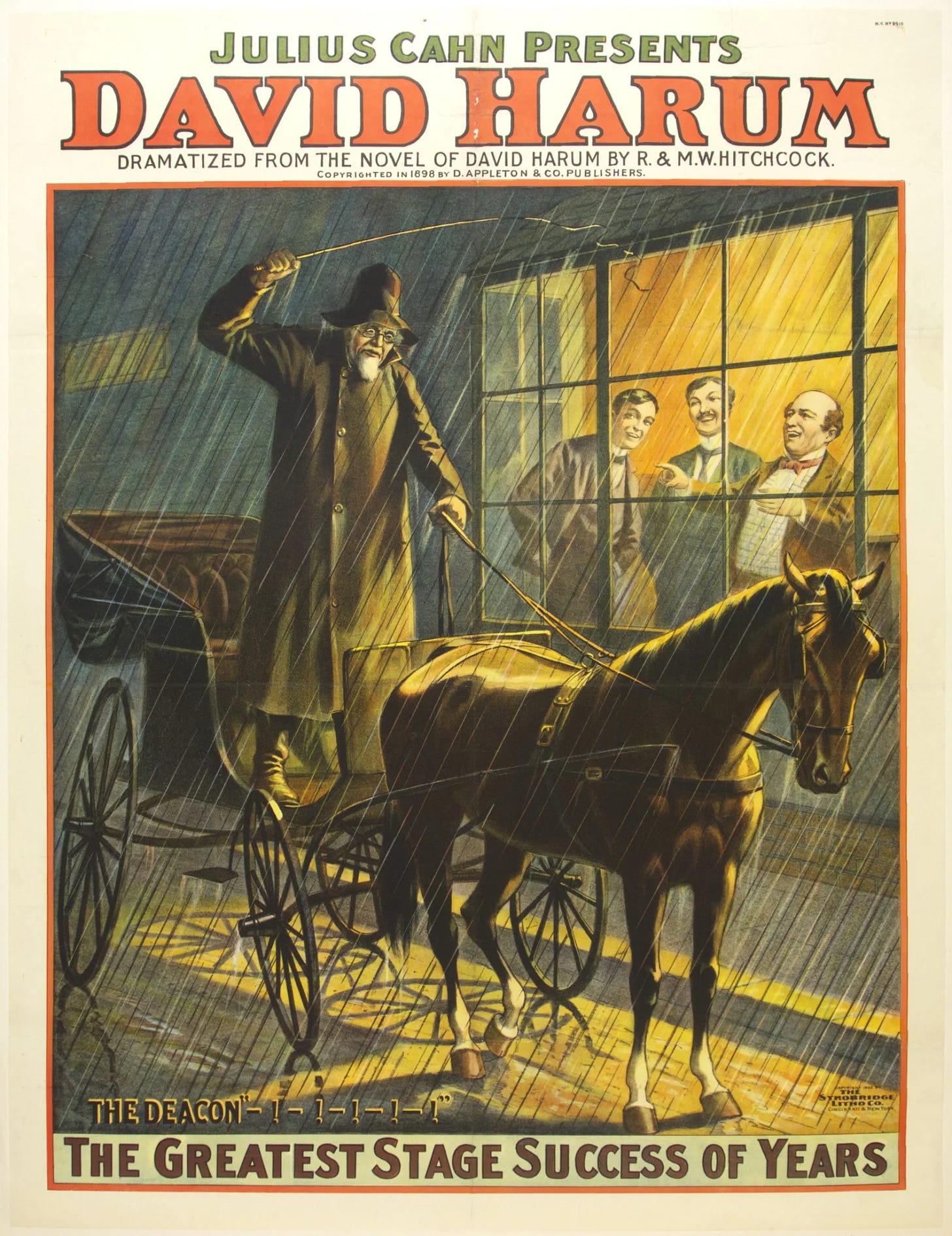

The habit of decision is still the great and commanding virtue. The undecided man, the wabbler, is to us the most pathetic and helpless of men. In “David Harum” there was a man who was always distressed when he had to make up his mind. He could not decide what shoes to put on in the morning, and he would get a black shoe on one foot and a tan shoe on the other foot, and then sit in misery, unable to decide which one to change. The New Testament is strong in its condemnation of the irresolute man. “Be no longer children,” it says, “tossed to and fro and carried about with every wind of doctrine, by the sleight of men, in craftiness, after the wiles of error.”7 “He that doubteth,” adds James, “is like the surge of the sea driven by the wind and tossed. For let not that man think that he shall receive anything from the Lord; a doubleminded man, unstable in all his ways.”8 How different and how much nobler is the man who can act, who is ever ready for instant and unhesitating action. “I hate this dreadful titter-fritteration of time; and I can’t stand it any longer,” said Samuel C. Armstrong during the war. He was used to decision, to doing things.

Few books have exerted more influence than John Foster’s essay on “Decision of Character.” That is our great need - such a habit of decision that we shall not waste time and strength in thinking about future decisions, or in devising reasons for not making present decisions, but shall do at once, without delay, what we see to be duty. When our fathers or employers say, “My boy, will you please do this,” we will say, whatever we are doing at the time, not “Excuse me for a moment please,” not “I cannot just now,” but “Yes, sir,” and do it without loitering. And we need the habit of decision not only as to acts, but also as to character, so that we shall be firm and positive and straight-acting. Some people are this way. They know how to make up their minds and to do directly what they have minded to do. And others are wabblers and hesitators.

III. Deciding Not to Wabble

Are you ready to build the habit of decision?

Perhaps we say: “Yes, we are among the weak. How can we acquire the habit of decision?

Speer’s suggestions to build this habit (below):

Conclusive thinking on our problems.

Focus our attention on virtue, truth and things that are good.

Practice making decisions.

Set out to do things for others.

Know that God will make the change in us.

A house needs a foundation. So does a character. Or rather the house is the foundation plus the structure built upon it. The character runs down, too, to include the foundation. If we want characters of decision we should lay the physical basis for them in clean, active, swift-answering bodies. We can give ourselves a good, wholesome discipline to this end by taking our bodies in hand. With many great men early poverty and necessity did this service for them, and frugality and hard work gave them tough, well-knit, well-purged bodies. But deliberate choice can take the place of necessity. Paul tells us he took his body in hand and disciplined it. “I buffet my body,” he says, “and bring it into bondage.”9 A governed will is not likely to live in an ungoverned body. An alert, determined, quick-working will is more at home in a body held in subjection and taught obedience.

We can help ourselves to become resolute and decided by doing conclusive thinking on our problems. We need to make up our minds on fundamental things and to keep them made up. There are many questions about which we do not need to bother ourselves, and which should not bother us. These we can postpone. But there are others which lie at the very root of things. The questions of the supremacy of truth, of our duty to God and man, of the divinity of Christ, are central questions. We should think of them until we are clear about them, and we should build solidly upon our convictions of truth and act fearlessly in accord with them. If we have no convictions we shall have little character. Decision in conviction will produce decision in character.

If we fix our attention rigidly on virtue, on truth, on things that are good, we shall find that such thinking breeds decisiveness of action and character. Our wills are given to us for the purpose of directing our thoughts. “The point to which the will is applied is always an idea,” says one of our leading psychologists. “The only resistance which our will can possibly experience is the resistance which such an idea offers to being attended to at all.” If, accordingly, we will think of good things and of doing good things, and will, as we can, refuse to let our attention turn to bad things or to not doing good things, the rest will take care of itself, or, rather, God who is working in us will take care of it. Paul knew this when, in the counsel he gave the Philippians, he bade them simply to take care of their thoughts. “Whatsoever things,” he said, “are true, whatsoever things are honorable, whatsoever things are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely, whatsoever things are of good report; if there be any virtue, and if there be any praise, think on these things.”10 If they thought thus first, then they would do what he bade, and the God of peace and strength would be with them - the God of decision.

Also we can help ourselves by practice. We can set ourselves by practice to make a decision a habit of our life. Professor James has told us how to acquire the good habits we desire: (1) Make automatic and habitual, as early as possible, as many helpful actions as we can. Get into the way of settling things decisively. (2) We must launch ourselves with as strong and decided an initiative as possible. The new Christian must openly and bravely confess Christ. This will make him surer in his discipleship, and it will make him a firmer and more dauntless character. (3) Never suffer an exception to occur until the new habit is securely rooted in your life. Following this rule with any good habit we wish to acquire will breed decision. (4) Seize the opportunity to act on every resolution you make and every prompting you may experience in the direction of the habits you aspire to gain. (5) Keep the faculty of effort alive in you by a little gratuitous exercise every day. “The man who has daily inured himself to habits of consecrated attention, energetic volition, and self-denial in unnecessary things, will stand like a tower when everything rocks around him and when his softer fellow-mortals are winnowed like chaff in the blast.”

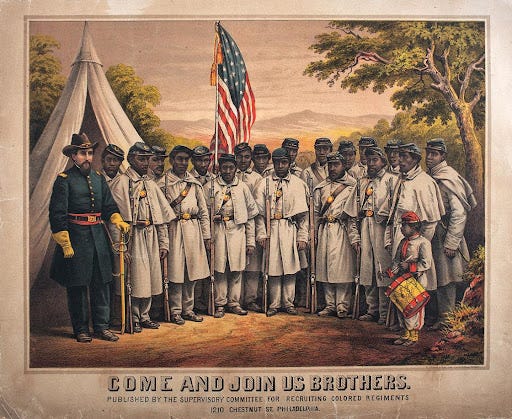

Unselfishness is a great help to decisiveness of character. It is easier to think quickly for others than it is for ourselves, and if we will set out to do things for other people we will find that we can be decided for them where we were irresolute for ourselves. And unselfishness is itself an essential part of decision. Decision of character involves readiness to do for the right and to die for the right. It is that which marks us as men and that shows that we have achieved the manly character. General Armstrong’s negro troops sang this in “The Enlisted Soldier”:

We want no cowards in our band

That will their colors fly,

We call for valient-hearted men

Who’re not afraid to die.

They look like men. They look like men.

They look like men of war.

All armed and dressed in uniform

They look like men of war.

Are we such men or do we only look like them?

And lastly, the unflinching Christ, who never hesitated, but met all, can take us and make us his. His living Spirit, which wrought in Simon Peter, who denied him at the taunt of a girl, but a few days later faced the multitude in his name, and died at last in his service, can work also in us the same mighty change from weakness to decisions. Shall we not be given freedom to do it?

Revelation 3:15-16.

In this case Speer is referring to the King James Version. In the NIVUK translation that I am using it occurs twenty-two times. But this doesn’t defeat his main point.